How Liberty Media boosted F1 to commercial success 🚀

Part 3: COVID, financial growth and looking to the future.

This post is the third and final in a three-part series on Libery Media’s growth strategy for F1 since its takeover in 2017. Read the first post here and the second post here.

F1’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

One eventuality that wouldn’t have been in Liberty’s plans when they became custodians of F1 in 2017 was the arrival of a global pandemic three years later.

The first scheduled race of the 2020 season, the Melbourne GP due to be held on 15th March 2020, was cancelled after the teams had already arrived. Subsequent races were also cancelled as the scale of the pandemic, and governments’ responses to it, became apparent.

Instead, the season opener took place on 5th July in Austria and 17 races, out of the originally planned 22, were held. Things would have been different under F1’s former leadership, as Bernie Ecclestone and Max Mosley called for the season to be canned. However, the new management, put in place by Liberty, as well as the teams and promoters, persevered and managed to salvage the season.

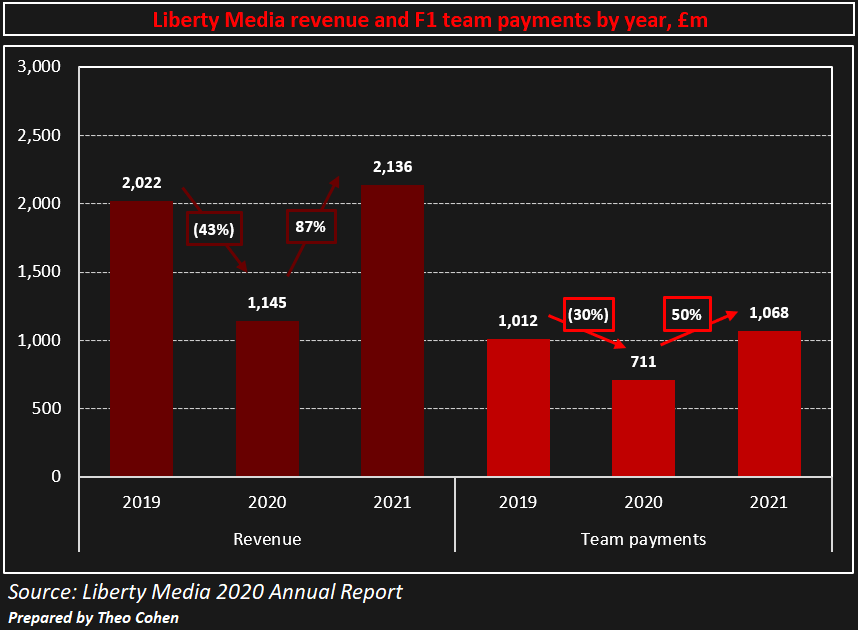

Liberty’s financial statements from 2020 show the scale of the crisis, as the company bore the brunt of the revenue decline to keep the teams afloat.

Revenues dropped by 43% from 2019 levels while team payments only decreased by 30%. The difference between these percentages indicates that Liberty did not pass on all of its losses to the teams.

Liberty implemented other practical measures to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on teams. The update to technical regulations planned for 2021 was postponed until 2022 allowing teams to cut development costs. As explained in my last post, the cost cap was also reduced to help smaller teams struggling as a result of the pandemic.

The COVID pandemic continued to impact F1 into the 2021 season, however the sport also showed signs of recovery. Several races were rescheduled, cancelled and replaced by others in the calendar. Crowds returned, with an estimated total attendance of 2.4 million over the course of the season. This marked a significant decrease (c.40%) from pre-COVID figures of 4.2 million, but it demonstrated a strong demand for F1 races despite the ongoing pandemic.

Financially, meanwhile, F1 showed a full recovery as the 2021 season produced more revenue for Liberty than pre-pandemic seasons and handouts to teams increased above 2019 levels.

By the 2022 season, the only remaining inconvenience of the pandemic was travel restrictions, and by 2023 the F1 calendar returned to normal. Despite doomsday predictions at the onset of the pandemic, Liberty’s F1 operations only recorded a loss in one year (2020) and not a single F1 team folded.

Liberty’s revenue growth

Liberty CEO Greg Maffei recently stated that Liberty is “here to play the long game” with respect to its stewardship of F1. When Liberty eventually decides to cash out, it’ll hope to realise a considerable return on its investment. The indicators from its financial statements, as well as those related to fan engagement and viewership outlined in my first post, suggest that Liberty may have substantially increased F1’s value already.

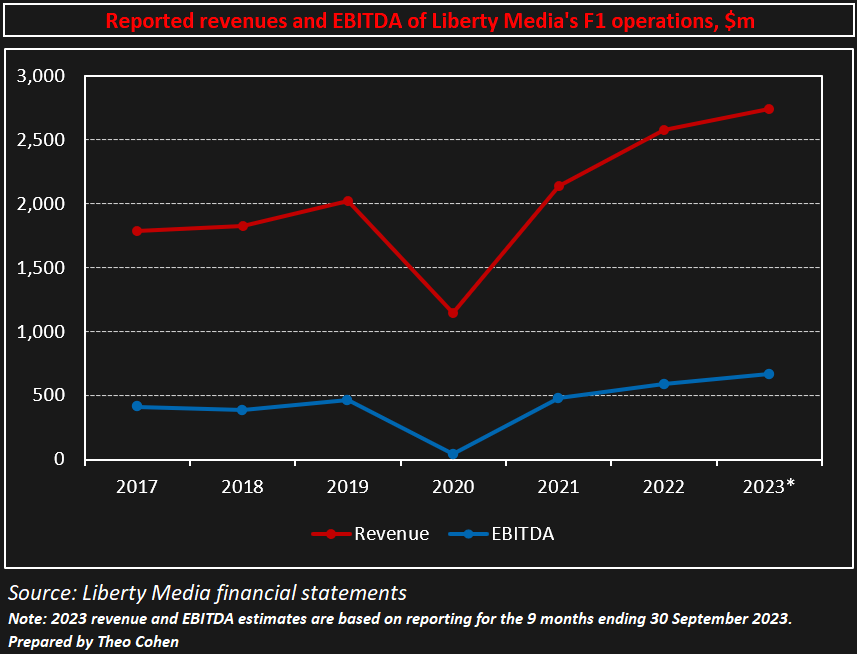

Total F1 revenue has increased in every year of Liberty’s ownership (excluding 2020 when the COVID pandemic had a devastating effect on the sport). Projected revenue for the 2023 season is 54% higher than in 2017, the year in which Liberty acquired a controlling interest in F1.

This is a remarkable turnaround for a sport that appeared to be in such a deep rut in 2016 that its de facto leader of the last 40 years, Bernie Ecclestone, stated that “Formula One is the worst it has ever been”.

Moreover, F1’s EBITDA has grown in four out of five non-COVID years under Liberty’s ownership, with a total increase of 61% over the entire period. This indicates that Liberty’s management has increased the operating cash flows available to F1, a strong indicator of value.

EBITDA is an acronym that stands for “earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation”. This measurement is often used in valuations since it is a good indicator of the operational profitability of a company.

New teams and revenue streams

Unsurprisingly, given F1’s recent growth, and soaring team values, F1 outsiders want to get in on the act. F1 rules would allow up to 12 teams to compete in the sport, and in October 2023 the FIA, which serves as the sport’s governing body, approved an Andretti-Cadillac F1 team application to join the paddock in 2025 or 2026.

However, last week, F1’s management, whose agreement was also required for Andretti-Cadillac’s involvement, rejected Andretti-Cadillac’s application for entry in on the basis that “the presence of an 11th team would not, on its own, provide value to the Championship.”

Many of F1’s existing teams vehemently opposed the introduction of a new team due to its implications for their revenues and, to a lesser extent, valuations. While F1 management stated that the “assessment did not involve any consultation with the current F1 teams”, it recognised that it should take into account the entry of an 11th team on “all commercial stakeholders”.

Effectively, the teams would have had to share the same prize pool with one extra participant, which would reduce each team’s payout. Andretti-Cadillac, a US-based team, disagreed with this premise. It argued that its involvement would have had a net positive effect on F1’s revenues, due to additional exposure, and marketing spend from Cadillac generating more sponsorships and revenue for F1. This additional revenue would be passed down to the other teams.

The other teams were understandably sceptical of this argument; there are already 10 of them, including behemoth brands such as Ferrari and Mercedes and an American team in Haas.

Damningly for Andretti-Cadillac, F1 management determined that “[w]hile the Andretti name carries some recognition for F1 fans, our research indicates that F1 would bring value to the Andretti brand rather than the other way around.”

Further, in confirmation of F1’s focus on competitive balance, it stated “The most significant way in which a new entrant would bring value is by being competitive. We do not believe that [Andretti] would be a competitive participant.”

F1 has, however, left the door ajar for 2028 entry for an Andretti-Cadillac car powered by a General Motors engine - Andretti’s application had included a plan to integrate the car with a General Motors engine in due course, but not from the team’s inception.

At present, there are just four engine suppliers in F1, each of which corresponds to a team. The desire for more suppliers is also driven by a want to check the growing power of the current engine manufacturers and to prevent the sport from becoming too dependent on a small number of suppliers.

Furthermore, the 2021 Concorde Agreement reportedly includes a clause which reduces the revenue proportion shared with the teams once total revenue rises above a certain number. Therefore, the marginal gain to F1 teams of extra revenue for F1 as a whole is less now than it would have been a few years ago when revenue may have been below this limit.

If Andretti-Cadillac had got the green light to join F1, it would have had to pay a $200m dilution fee to be shared around the existing teams, which is intended to compensate the teams for lost future revenue. This fee was negotiated as part of the 2021 Concorde Agreement, in the context of the chaos caused by the COVID pandemic, and was justified at the time as being close to the amount Williams had recently been sold for.

This dilution fee, paid for by a new joiner, has implications for team values. A prospective investor in a team could argue that they could pay the $200m dilution fee, invest some capital into R&D, and they’d have an F1 team. Hence, the total start-up figure sets a lower bound on team valuations.

Teams believe the F1 landscape, and their team values, have changed significantly since 2020 such that the dilution fee should be hiked to $600m. No doubt this fee will be an item for negotiation ahead of the 2026 Concorde Agreement and should Andretti-Cadillac enter the paddock in 2028, it’s likely that it will have to cough up more than $200m.

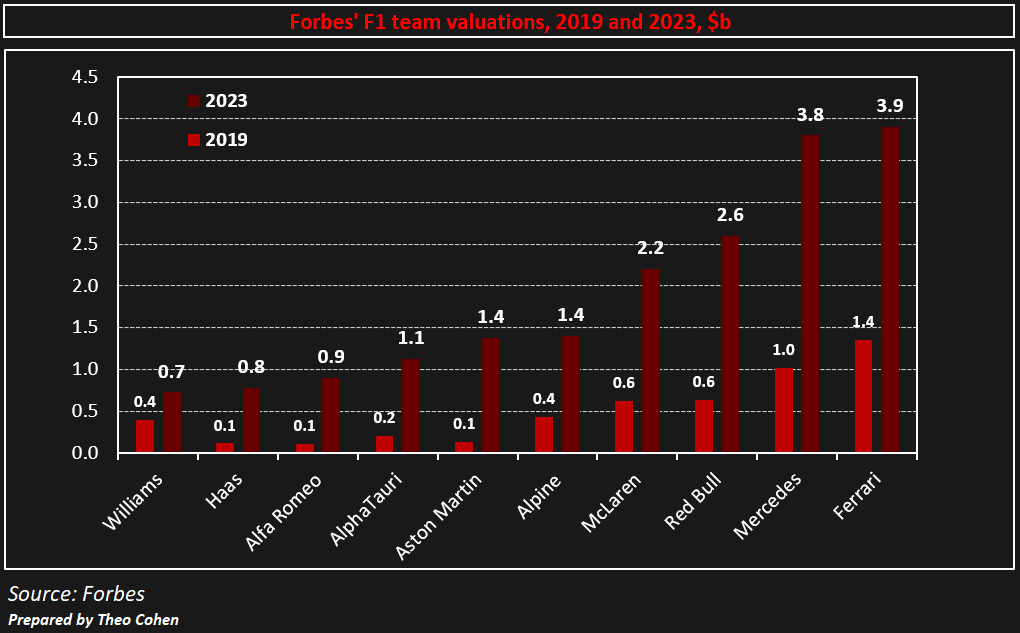

Owners are keen to protect their team values due to the giant leaps the values have made during the period of Liberty’s ownership.

Alpine, which finished 4th in the 2022 Constructors’ Championship and 6th in 2023, recently sold a 24% equity stake in its business for €200m. This transaction valued Alpine at around €900m. Prior to this transaction, the last time the team had changed hands was in 2015 when Renault paid just £1 to buy what was then the cash-strapped Lotus F1 team.

Alpine was rebranded from Renault to Alpine in 2021 to promote Renault’s sports car brand, Alpine.

F1’s cost cap has been specifically singled out as having had a transformative effect on team value. There is the hope that the cap will make racing more competitive, and allow teams other than the sport’s big hitters to compete for regular podium finishes.

However, more importantly for prospective investors, the cost cap has introduced regularity and certainty to each team’s yearly cash flows. The acerbic Guenther Steiner, ex-Haas Team Principal, and star of DTS, put it well, “[b]efore, someone investing in a race team didn’t know if you would spend $200 million a year or half a billion a year. There was everything in between.”

While Zak Brown, McLaren CEO, reserves some credit for his team going from losing as much as “nine figures” to being a “profitable sports team”, he gives “a lot of credit to Liberty that when they came in they established a cost cap.”

The increased financial sustainability enforced by the cost cap, as well as the reduced year-on-year uncertainty in capital investment, has made F1 team’s more investable, and values have grown accordingly.

Plainly, Liberty’s management of F1 has been hugely beneficial to team owners. Liberty itself has also benefitted from its astute management. Should it decide to sell F1 now, it would undoubtedly receive a lot more than the $4.4b it paid for F1’s equity in 2017. Indeed, Forbes put a $17.1b figure on F1’s enterprise value in January 2023, 114% higher than the $8b enterprise value implied by Liberty’s purchase.

Furthermore, the 2023 Las Vegas Grand Prix offered an insight into a potential avenue for revenue growth for F1. Normally, the commercial rights holder, F1 itself, charges fees to the various circuits, known as race promoters, around the world to host and operate grand prix. This revenue stream accounted for 23% of F1’s total revenue in 2022 and translates to each promoter paying $27m on average.

Although the terms of the contracts with race promoters are not publicly available, it’s understood that the promoters recoup their outlay through ticket sales, local sponsorships, hospitality and on-site activations. This business model ultimately puts a ceiling on F1’s revenue.

That said, it simultaneously reduces downside risk and logistical and operational complexity for F1, by passing on the responsibility for running races to promoters. However, the 2023 Las Vegas Grand Prix marked the first time that F1 and Liberty had taken the act of race promotion in-house.

In 2022, Liberty bought a 39 acre plot of land for $240m to locate a permanent pit and paddock complex for the Las Vegas GP. While an expensive exercise, this complex serves as F1’s permanent home in the city, and removes the cost and logistical challenge of building a temporary pit complex every year. Since the race has approval to run through 2032, it seems that this building was a shrewd addition, and is a sign of F1’s commitment to making this new business model work.

With 315,000 attendees and the highest ticket prices of any grand prix, as well as lucrative sponsorships with Heineken, American Express and Las Vegas establishments Caesars and MGM among others, F1 will have earned considerable revenue from the event.

We will have to wait for Liberty’s next earnings release and annual report to see its impact, but we can already say for sure that the Las Vegas Grand Prix will not be leaving the calendar any time soon.

It marked the convergence of the many strands of Liberty’s strategy since its acquisition of F1 in 2017: drawing crowds inspired by DTS to an enthralling show driven by competitive balance in the entertainment capital of the world, all run in-house by F1 and Liberty with renewed creative direction.

Indeed, should it prove to have been a success, it could be the trigger for a widespread change to F1’s business model.

In the six years since Liberty’s acqusition in 2017, F1 has survived a global pandemic, produced one of the most controversial sporting finales of the last decade, introduced the world to Guenther Steiner (and summarily dismissed him), sent race cars reverberating down the Las Vegas Strip, and more than doubled in value.

It is unclear whether the next six years will see umpteen more Verstappen poles, a Mercedes resurgence or another team’s emergence to the front of the grid. But for the sake of F1’s viewers, and its own back pockets, Liberty will certainly hope that Red Bull’s rivals can chase them down.

This post is the third and final in a three-part series on Libery Media’s growth strategy for F1 since its takeover in 2017. Read the first post here and the second post here.

Please ❤️ this post and subscribe to my substack if you enjoyed this series on F1!

Sources

The Athletic;

Autosport.com;

Motorsport;

BlackBook Motorsport;

Joe Pompliano;

Companies House;

Nielsen;

BuzzRadar;

Forbes;

Formula One;

Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile;

Liberty Media financial statements;

Sportico;

Morning Consult;

Financial Times;

Racefans;

Wieden + Kennedy;

The Guardian.

Throughout this article, I use the terms “Liberty” and “F1 management” interchangeably. Although there is a difference between the two terms, it’s safe to assume that F1’s management and strategy since Liberty’s takeover have been guided and set by Liberty.