It may sound like a truism, but the primary determinant of F1’s commercial success is the races themselves. Even if the branding, marketing, sponsorships, streaming, presenting, events and broadcasting are perfect, if the races are boring, people are not going to tune in.

BuzzRadar’s social media analysis identified that F1 is most interesting when there’s genuine competition at the front of the grid.

Liberty, a US-based company and owner of the Atlanta Braves MLB team, will be acutely aware of the importance of competitive balance to generating value for the shareholders of that competition. One of the keys to the success of major American sports leagues, especially the NFL and NBA, is the pursuit of competitive balance through salary caps and player drafts.

Since the takeover, Liberty has attempted to level the F1 playing field through three separate pieces of regulation.

This post is the second in a three-part series on Liberty Media’s growth strategy for F1 since its takeover in 2017. Read the first post here and the third post here.

The 2022 Technical Regulations

An extensive technical overhaul had been planned for the 2021 season but was postponed due to the uncertainty caused by the COVID pandemic. The renewed regulations took effect ahead of the 2022 season instead.

These regulations concerned aerodynamics, fuel and safety. They aimed to reduce the disadvantage of chasing cars, bringing the pack closer together and increasing competitiveness for more exciting racing.

The details of these regulations is beyond my expertise and the scope of this series but there is plenty of considered analysis out there, including this Sky Sports article and this more technical article from Racecar Engineering.

The Concorde Agreement and revenue distribution

The contract between the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), the F1 teams and the companies that form the F1 organisation itself is known as the The Concorde Agreement.

The first version of this agreement was signed in 1981, while the two most recent iterations were signed in 2013 and 2021, the former negotiated while F1 was under the management of CVC/Ecclestone and the latter under the management of Liberty.

Since it took over F1, Liberty has outlined its desire for a more equitable distribution of funds to constructors and it delivered with the 2021 Concorde Agreement.

2013 Concorde Agreement

Before continuing this section, I must caveat it with an acknowledgement that the terms of each iteration of the Concorde Agreement are kept strictly secret by the contracting parties. The information below should serve as guidance rather than gospel.

The most reliable information on the terms of the 2013 Concorde Agreement is provided by Dieter Rencken, a highly respected F1 journalist who was most recently an advisor to the President of the FIA.

He penned an article in 2017, forecasting the central F1 financial distributions to each team in that year, which are determined by the terms of the 2013 Concorde Agreement.

According to Rencken’s forecast, at the start of the 2017 season, F1’s estimated turnover was $1.83b, with underlying revenues (excluding non-recurring revenue) of $1.38b. The share of underlying revenue distributed to teams was around 68%, which equates to $940m.

This forecast is pretty close to the actual value of revenue distribution provided in Liberty’s financial statements for 2017: $919m. I have adjusted the amounts from Rencken’s forecast to reflect the difference between his forecast and the actual revenue distributed to teams.

Money was distributed to teams on a number of different bases, which are summarised below.

Column 1 payments

Around 34% of the money was split evenly among the teams who finished in the top ten of the constructors’ championship in two of the previous three seasons.

Since Haas made its debut in the 2016 F1 season, and therefore had only competed in one season at the time, it did not receive a Column 1 payment in 2017.

Column 2 payments

Another 35% was distributed based on teams’ performances in the constructor’s championship. Mercedes, which won the championship, received $59.6m while Sauber, which finished bottom, received only $12.7m.

That means Mercedes Column 2 payment was 4.7x greater than Sauber’s payment.

Long-standing team bonus

Ferrari is the oldest surviving and most successful F1 team, having competed in every world championship since 1950. Since Ferrari is so important to and synonymous with F1, it receives a huge 'long-standing team bonus’.

In 2017, the value of the bonus was $66.5m. That was 7% of all the money distributed to teams and more than the total amounts received by four teams (Toro Rosso, Renault, Sauber and Haas).

Constructors’ Championship Bonus

This bonus, received only by Ferrari, Mercedes, Red Bull and McLaren, was negotiated by Bernie Ecclestone to persuade F1’s biggest teams to commit to the competition.

Its value fluctuates slightly with performance. In the 2016 season, Mercedes and Red Bull finished 1st and 2nd while McLaren finished 6th. As a result, Mercedes and Red Bull received $38.1m, while McLaren received $29.3m.

Other bonuses

Red Bull negotiated a bonus with Bernie Ecclestone in the 2013 Concorde Agreement as the first of the big teams to make a long-term commitment to F1.

Understandably, Mercedes then asked for a similar bonus, as a team comparable in size to Red Bull. Ecclestone agreed, subject to the condition that Mercedes needed to win consecutive constructors’ championships before the bonus payments started.

Ecclestone might have thought he’d got a good deal, since Mercedes had never previously won the constructors’ championship. However, they went on to win back-to-back championships at the first time of asking in 2014 and 2015 (and every subsequent year until 2022).

Williams, having competed in its first race in 1977, received a heritage payment of approximately $10m.

2021 Concorde Agreement

While Column 1 & 2 payments promote fairness and competitive success, the other bonuses negotiated in the Ecclestone era reinforced entrenched financial inequalities within the sport.

The result was that top-earner Ferrari earned 3.7x as much as Sauber (which would’ve been the bottom earner but for Haas’ non-receipt of Column 1 payments) in 2017 from F1’s central payouts.

The 2021 Concorde Agreement presented by Liberty aimed to address some of the inequalities of previous agreements. According to Christian Horner, Principal of Red Bull Racing, negotiations were “a lot less fun” and “what [ex-Liberty CEO Chase Carey] put on the table was pretty much what was signed”.

It’s not completely clear whether Mercedes managed to obtain special terms, with contrasting noises coming from Toto Wolff, Mercedes Team Principal, and Liberty insiders.

It is the consensus among F1 journalists that those teams that used to get additional payments will still get them but that the proportion of the pot allocated to bonuses has been reduced. Jonathan Noble, a member of the FIA Media Council, has provided the most reliable information on the distribution of prize money dictated by the 2021 Concorde Agreement . He says that bonus payments now “account for around 25% of the total prize pot”. That’s a reduction from 2017, when bonuses accounted for 31%.

According to Noble, Column 1 & 2 payments have effectively been replaced by a sliding scale whereby the top placed team in the previous season’s constructors’ championship receives 14% and the bottom team 6%. The other teams receive amounts in equal increments in between.

The result is a distribution of the non-bonus funds that looks fairly similar in 2023 to that in 2017. The difference of course is that 75% of the prize money is non-bonus, compared to 69% previously.

Assuming a $1.33b total prize money pot in 2023 based on Noble’s reporting, $79m more is distributed to teams based on competitive success than would have been under the terms of the previous Concorde Agreement.

Ferrari’s "long-standing team bonus” has reportedly been reduced to 5% of the total pot, compared to 7% in 2017. Other teams that have achieved success in the constructors’ championship in recent years qualify for bonuses (i.e. Mercedes and Red Bull). Although it is not clear how far back “recent” goes.

There is also understood to be a separate pot based on extra payments for teams that have finished in the top three of the constructors' championship in the previous 10 years. This includes Ferrari, Mercedes, Red Bull, McLaren and Williams, each of the teams which had earned a bonus per the 2013 Concorde Agreement.

In the 2021 Concorde Agreement, the first negotiated by Liberty, the old guard have maintained receipt of greater financial rewards than their less established peers, although the percentages have shifted in favour of the newer teams. Moreover, Liberty appears to have held a resolute bargaining position, which sets a strong precedent for future negotiations. I expect that Liberty will aim to chip away further at the arbitrary historic bonuses in pursuit of a level playing field; it has set itself up well to do so.

The Cost Cap

The final leveller introduced by Liberty since taking over F1 is a cost cap which limits the amounts teams can spend each season. The cost cap is administered by the FIA but Liberty played the crucial role in negotiating the terms of the regulations with F1’s largest stakeholders.

Chase Carey, the Liberty appointed ex-F1 boss, had argued that wider competition should be promoted by limiting spending on cars and redistributing revenue paid to teams. Both these goals were achieved through the FIA’s 2021 F1 Financial Regulations (the cost cap) and the 2021 Concorde Agreement respectively.

Liberty’s own CEO, Greg Maffei, heaped praise on Carey for the significant achievement, saying:

Bernie Ecclestone and Max Mosley after the '09 recession tried to get a cost cap in, and couldn't get it done… We got there. Dumb Americans, what do we know about the sport? We say we want to get it done, and they laugh at us. Chase gets it done, full credit - Chase and team.

Greg Maffei, President & CEO, Liberty Media

Indeed ex-Ferrari CEO, Sergio Marchionne, threatened to pull the Ferrari F1 team from the competition after the 2020 season (the final year governed by the 2013 Concorde Agreement), and Toto Wolff, Mercedes Team Principal, echoed those sentiments, saying “Marchionne is a no bullshit guy and I think Ferrari and Mercedes pretty much share their view of the DNA of the sport”.

Wolff argued that 2021 spending should not be simply capped at, say, $150m, roughly half the budget of the top teams. Instead, he suggested that there should be an incremental reduction in the cost cap to allow teams to adapt.

In June 2019, Liberty broke the impasse, negotiating a $175m simple cap for the five seasons from 2021-25, which represents the period covered by the 2021 Concorde Agreement.

Then in 2020, the economic consequences of the COVID pandemic accelerated the need for a reduction in team expenditure, as teams faced a calendar with fewer races in the 2020 season and an uncertain future thereafter. Hence, the sport agreed to a limit of $145m for 2021, with incremental reductions in subsequent seasons - $140m in 2022 and $135m in each season thereafter.

The cap is set on the basis of a 21-race championship. For each race above/below that threshold the cap is increased/reduced by $1.2m.

The cost cap governs expenditure related to car performance, including:

car parts (excluding the engine);

other elements necessary to run the car;

most of the team personnel costs;

garage equipment;

spare parts; and

transport costs.

Of these categories, the largest amount is spent on the development and manufacturing of car parts. The cost cap requires teams to allocate budget and time to areas they deem the most important, preventing richer teams from throwing money at all areas and producing superior parts.

However, many areas of F1 expenditure are excluded from the cost cap, including:

marketing, HR, finance and legal activities;

costs related to heritage asset (i.e. old F1 cars) and non-F1 activities;

driver compensation and travel costs, and costs related to the three highest cost non-driver employees;

employee bonuses up to 20% of total remuneration;

engine costs;

and more…

There are also separate technical regulations which relate to engine construction and costs. These are far more complex because some teams make their own engines, such as Mercedes, while others buy them in from other teams, such as McLaren who buy from Mercedes.

There are only four teams which could realistically break the cost cap based on previous expenditure levels: Ferrari, Mercedes, Red Bull and McLaren. Of these, all but Ferrari file their financial statements with Companies House in the UK.

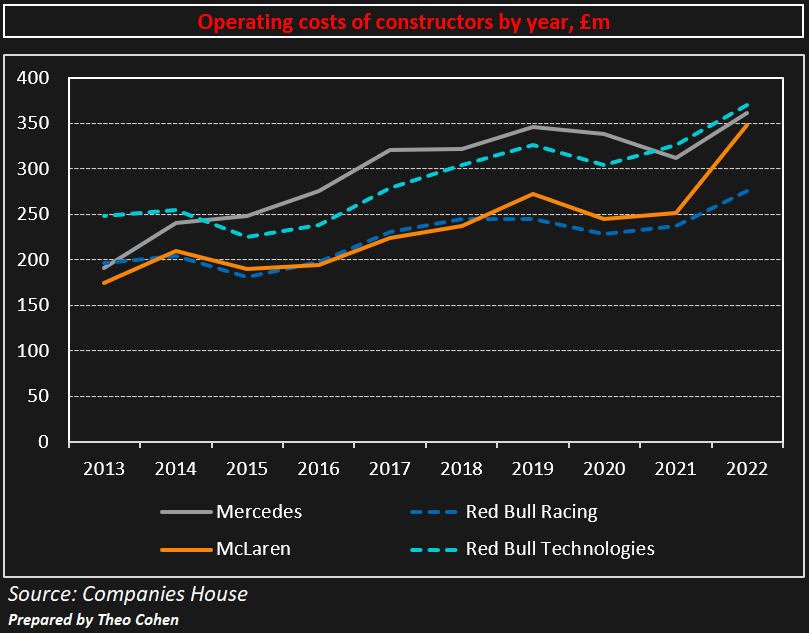

Each team’s operating costs include relevant costs to the cost cap, so it’s surprising to see that they have increased since the introduction of the cap. Some of this increase may be explained by significant inflation, especially in 2022.

Of course, it is possible that teams have decreased their spending on relevant costs but increased their spending on excluded costs by a greater amount. However, it may just be the case that the cost cap is too high, such that the biggest teams have not had to reduce their spending as much as the regulators had intended.

It should be noted that the teams’ costs aren’t directly comparable with each other, due to different business models and group structures. The analysis is complicated by the division of Red Bull’s F1 operation between Red Bull Racing, which manages the F1 team, and Red Bull Technologies, which designs and manufactures the the parts.

In addition, the company which operates the Mercedes F1 team is also home to an Applied Science division which performs engineering consultancy projects for third parties based on F1 principles.

Ultimately, without further financial statement granularity, it’s impossible to know how top line cost items (operating expenses and cost of sales, for example) break down, and to what extent the cost cap has curtailed spending among the big teams.

Cost cap breaches

Red Bull is the only team so far to have breached the cost cap, having overspent by £1.9m in 2021. This breach, announced in November 2022, constituted a Minor Overspend (where relevant costs exceed the cost cap by <5%) for which Red Bull was handed a $7m fine and a 10% reduction in its aerodynamic testing allowance for the next 12 months.

At the time, Red Bull Principal Christian Horner called the aerodynamic testing penalty “draconian”, claiming that it would impact both the 2023 and 2024 cars. However his team went on to win the 2023 Constructors’ Championships by a massive margin.

Conversely, some of Red Bull’s rivals have argued that the punishment was not harsh enough. Lewis Hamilton claimed that a small overspend could have a significant effect - particularly in the 2021 season to which Red Bull’s breaches relate, in which Lewis Hamilton lost the Drivers’ Championship in controversial circumstances in the season finale in Abu Dhabi. Hamilton claims he could have won the title if Mercedes had spent an additional $300k on in-season performance upgrades.

Indeed, former F1 designer and current FIA director Nikolas Tombazis believes that the cap may have also contributed to a widening of the gap between Red Bull and others at the top since the 2021 season.

The problem with the financial regulations is… that if you're behind somebody, you can't just throw everything at it and make an upgrade.

In older times, some teams would occasionally start a season and be in a really quite bad place… I've been involved in such a situation, but then you just make a massive upgrade package… and you'd virtually redesign the whole car like crazy for three or four months…

The [current] financial regulations limit the amount of upgrades you can do. So, if somebody is further back, the recovery can be quite long and painful.

Nikolas Tombazis, Single Seater Director, FIA

Mercedes recent struggles are arguably the best evidence that the cost cap is preventing additional expenditure among the big teams, despite the increase in the team’s costs observed in their financial statements.

It is the generally accepted view that the cost cap may have helped to close up the rest of the grid but in doing so it may have opened up a gap at the front. Social media data showed a strong correlation between engagement and a highly competitive Drivers’ Championship. Hence, if the cost cap perpetuates Red Bull’s dominance, it may do more harm than good.

That said, it is clear that the cost cap remains under constant review, having been updated this year to close a loophole related to the transfer of IP from companies’ non-F1 work to the F1 team. While the introduction of the cap was a big first hurdle to overcome, Liberty must ensure that it continues to work for its intended purpose.

This post is the second in a three-part series on Liberty Media’s growth strategy for F1 since its takeover in 2017. Read the first post here and the third post here.

Please ❤️ this post if you enjoyed it!

Sources

The Athletic;

Autosport.com;

Motorsport;

Joe Pompliano;

BlackBook Motorsport;

Companies House;

Nielsen;

BuzzRadar;

Forbes;

Formula One;

Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile;

Liberty Media financial statements;

Sportico;

Morning Consult;

Financial Times;

Racefans;

Wieden + Kennedy;

The Guardian.

Throughout this article, I use the terms “Liberty” and “F1 management” interchangeably. Although there is a difference between the two terms, it’s safe to assume that F1’s management and strategy since Liberty’s takeover have been guided and set by Liberty.