Chelsea was sold to Todd Boehly and Clearlake Capital for £2.5bn in May 2022. Newcastle was finally prised away from Mike Ashley’s grip in a deal worth £305m in October 2021. Meanwhile, Liverpool and Manchester United are seeking investment, and Manchester United’s owners, the Glazers, value the club at over £5bn.

So, how do owners, club finance experts and prospective buyers alike determine the value of a football club? There are a number of approaches, and I aim to describe, explain and evaluate each of them in this article series.

The first valuation technique I focus on is an assets-based valuation.

Summary of approach

An assets-based valuation approach aims to value a business based on its net assets value in the company’s balance sheet.

The fundamental accounting equation, and that which underpins double entry book-keeping, is Equity = Assets - Liabilities. Since net assets are Assets - Liabilities, this means the equity value of the company is equal to the net assets.

Asset-based valuation approaches often adjust the net assets value presented on the balance sheet to account for the current market value, rather than the book value, of the company’s assets. Balance sheet valuations of assets decrease over time due to depreciation and amortisation, so book values of assets are not often equivalent to fair market value.

Assets of a football club

An asset is a resource:

controlled by an entity as a result of past events; and

from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity.

Non-current assets

Also known as fixed assets, non-current assets are any assets that are not current assets (more on those later).

Non-current assets are further divided into two categories: tangible and intangible assets.

Tangible assets

These are often grouped together as “Plant, property and equipment”. They are assets which have physical substance, such as office buildings, machinery or vans.

The cost of a tangible asset is spread over its useful economic life, which must often be estimated, and charged against the company’s profits as a depreciation expense. There are multiple methods of depreciation, and the method which is applied depends on the asset at hand. A non-current asset often has a scrap value, a worth when it is deemed no longer usable, which must be considered as the base value in the depreciation calculation.

At most football clubs, the largest tangible asset is the stadium (although some clubs in recent years came to questionable agreements with their owners to purchase and lease back their stadiums for Financial Fair Play reasons). However, the balance sheet values of football stadiums are often significantly lower than their true market values.

Tangible fixed assets are generally recorded on the balance sheet at historical cost less depreciation. Buildings are depreciated at a slower rate than other fixed assets. For example, a car might be depreciated on a straight line basis by 10% each year whereas the straight line rate for a building could be around 2%. The book value of a new stadium such as the new Tottenham Hotspur Stadium may bear some resemblance to its true market value. But consider older stadia such as Old Trafford and Craven Cottage which have existed for many decades, for these stadia depreciation will have significantly reduced the book value. Hence, most older stadia are undervalued on the balance sheet.

Intangible assets

Intangible assets are defined as “identifiable non-monetary assets without physical substance.” For an asset to be identifiable, it must either:

be separable i.e. capable of being separated from the entity and sold; or

arise from contractual or other legal rights.

For most companies, the majority of intangible assets will relate to patent rights, trademarks, goodwill and licences etc. While lots of football clubs will own some of these assets, the intangible assets with the greatest book values for football clubs are player registration transfers.

This intangible asset represents the fee paid by the club (as well as external costs incurred in purchasing such as lawyers and agents’ fees) to acquire the exclusive registration of a player from another club. Essentially, these assets are the financial representation of a club’s players on their balance sheet.

Recalling the earlier definition of an asset (“a resource controlled by an entity as a result of past events from which future economic benefits are expected to flow”) and concurrently considering the definition of an intangible asset, a player registration transfer qualifies as an intangible asset by satisfying the following criteria:

control - the registration is exclusive, it restricts the ability of the other clubs to register the player;

past event - consideration (cash) transferred to the previous owner;

future economic benefits - contributes to the performance of the team on the pitch, generating income through prize money, commercial sponsorship and broadcast revenue; and

identifiable - arises from the contractual right of the club with the player.

Similar to the depreciation of a tangible asset, the amortisation of an intangible asset spreads the cost of the asset over its useful economic life. Fortunately, with player registration transfers, it is fairly easy for clubs to determine useful economic life - it is simply the length of the player’s contract. Hence, the amortisation fee per year is the transfer fee divided by the length of the contract.

When a player extends their contract, the remaining balance of their transfer fee yet to be amortised is spread over the new longer contract period.

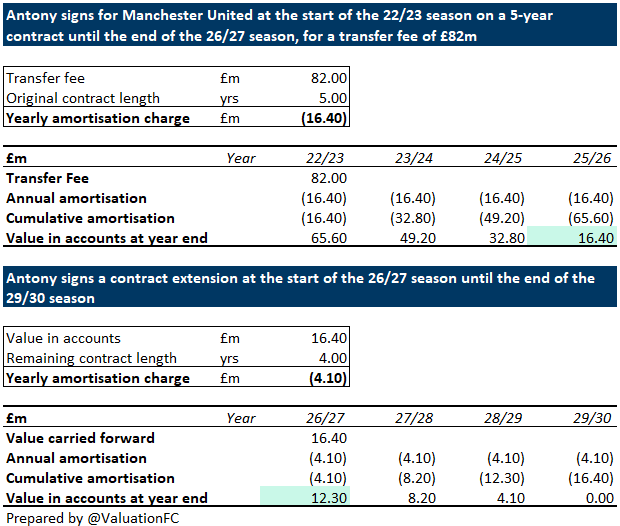

Let’s consider the transfer of Antony to Manchester United from Ajax at the start of the 22/23 season on a five year contract and assume that he signs a contract extension at the start of the 26/27 season.

At the end of the 25/26 season, with one year left on his contract, Antony’s book value to Manchester United is £16.4m. The following year at the end of the 26/27 season, now with three years left on his contract, Antony’s book value is £12.3m.

Although he has aged a year, and football clubs pay a premium for younger players, his book value does not reflect the reality that the club is in a much stronger bargaining position in the transfer market than the previous year due to the length remaining on his contract.

Antony’s £16.4m book value at the end of 25/26 reflects a low value due to his expiring contract and can be considered somewhat reasonable. However, a £12.3m value in 26/27 for a player previously purchased for £82m with three years remaining on his contract seems too low.

(For the purposes of this demonstration, I have assumed that Antony was transferred at the start of the accounting period ending at the end of the 22/23 season. In reality, amortisation is pro-rated over the portion of the accounting period for which the player is exclusively registered to the club.)

This example demonstrates how the value of player transfer registrations can often be undervalued when a player has renewed their contract.

A similar problem arises for players who come through a club’s academy. The registration of a player developed at a club’s academy would, for accounting purposes, count as an internally generated intangible asset. As per international accounting standards, the club cannot reliably determine the cost of “generating the intangible asset (i.e. the player) because it cannot be distinguished from the cost of maintaining or enhancing the entity’s internally generated goodwill or of running day-to-day operations.” It’s not necessary to explain what goodwill is here to understand the issue: a club cannot accurately determine its cost in producing one of its academy graduates. Internally generated intangible assets are not recognised on the balance sheet.

Hence, the values of players like Bukayo Saka, Phil Foden and Harry Kane do not appear on on the balance sheets of their respective clubs. This represents another way in which assets are undervalued on a club’s balance sheet.

The final consideration with respect to player registration transfers is the treatment of free transfers, in which a player’s contract has expired at one club and they are free to sign for another club with no consideration (cash or otherwise) transferred to their previous club. While these player registration transfers do qualify as intangible assets, they are recognised at cost which, in this case, is nil.

A further issue which may lead to the undervaluation of players on the balance sheet is inflation. According to a CIES Football Observatory report, between 2014 and 2019 the average inflation rate year-on-year for player transfers was 26%. Players’ book values, which are based on historical cost, do not reflect this inflation.

Finally, there are other intangible assets of football clubs that do not appear on the balance sheet for the same reason as academy players - they are internally generated intangible assets. Examples are the club’s brand, the loyalty of fans renewing season tickets, and databases of supporters’ information.

Using social media followers as a crude proxy for supporters, Manchester United had 171m followers across Facebook, Instagram and Twitter at the time of writing. This fanbase represents a large asset to the club, but is not represented on the balance sheet.

Each of these scenarios - contract extensions, academy graduates, free transfers and other internally generated intangible assets - all result in the undervaluation of intangible assets on the balance sheet. Therefore, assets-based valuations often produce a lower value than other valuation techniques.

Current assets

An entity shall classify an asset as a current asset when:

it expects to realise the asset or intends to sell or consume it in its normal operating cycle;

it holds the asset primarily for the purpose of trading;

it expects to realise the asset within twelve months after the reporting period; or

the asset is cash or a cash equivalent.

For a football club, current assets often include:

stocks of merchandise;

cash and cash equivalents (for example liquid investments); and

trade receivables (also known as debtors).

Trade receivables primarily relate to transfer fees yet to be received. Depending on the payment terms, these could be received at any time, however they are usually expected to be received within a year of the date of the transfer.

In the UK, if the amounts due after more than one year are so material that the absence of their disclosure on the balance sheet could cause the reader to misinterpret the financial statements, they must be disclosed on the balance sheet. Otherwise it is satisfactory to disclose the amount due after more than one year in the notes to the financial statements.

Liabilities of a football club

A liability is a present obligation of an entity arising from past events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow from the entity of resources embodying economic benefits.

Non-current liabilities

As you might expect non-current liabilities are those liabilities for which payment is not due for more than one year.

For football clubs, these are often loans taken out to fund infrastructure expansion, such as those taken out by Arsenal and Tottenham to finance the Emirates Stadium and the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium respectively.

Loans can be taken from a number of sources, but tend to be provided either by banks or the club’s owners. Often, the club’s owners will loan money to the club at a lower interest rate than that offered by a bank.

During his tenure as Chelsea manager, Roman Abramovich loaned Chelsea £1.6bn through the club’s parent company Forstam. The loan was interest free and allowed Chelsea to outspend their rivals in the transfer market, particularly before 2011 in the pre-FFP era. Other rivals with less benevolent owners could not compete.

Current liabilities

Current liabilities are liabilities for which payment is due within one year.

Often, this line on the balance sheet includes sums owed for player transfers. Depending on when the payments are due, moneys owed to other clubs for player transfers can be classified as current liabilities or non-current liabilities.

With transfer values so inflated in modern football, the total sum for a player transfer is often split into instalments on an agreed payment schedule. Consider the transfer of Enzo Fernandez from Benfica to Chelsea for €120m. If the sum is split into payments spread over 4 years, at the time of purchase, €30m (€120m / 4 years) will be classified in current liabilities and the remaining €90m (€120m / 4 years * 3) will be classified in non-current liabilities.

It is important to note a distinction here between payments and profits/expenses. As explained previously, the cost of a player transfer will be amortised over the length of the player’s contract (their ‘useful economic life’) and this will be the amount that profit is reduced by each year. Enzo Fernandez has signed a 8.5 year deal at Chelsea so the yearly amortisation charge - and hence reduction of profit - is €14.1m (€120m / 8.5 years). The payment to Benfica each year would be shown on the cash flow statement, but it would not have an impact on profits.

Example of an assets-based valuation approach

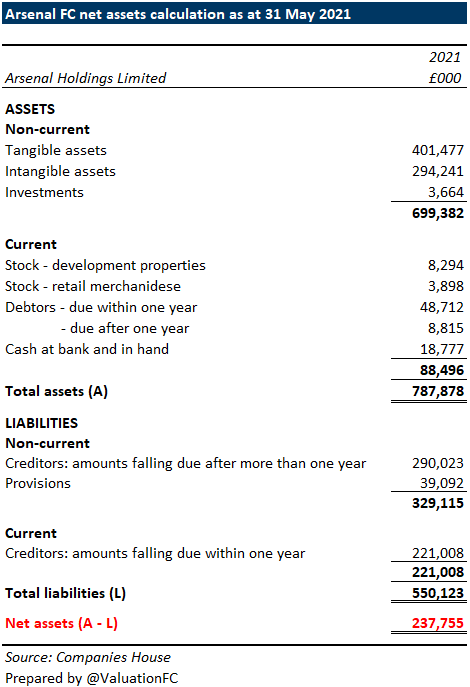

I demonstrate below a net assets calculation using the most recent financial statements of Arsenal for the year ended 31 May 2021. As at this date, the balance sheet shows that Arsenal had net assets of £238m.

The notes to the accounts show that the balance to the parent undertaking, KSE UK Inc. (i.e. Stan Kroenke), was £202m. Presumably, a willing buyer would have to pay this sum to KSE in order to relieve the debt.

Therefore, according to an assets-based valuation method, Arsenal is worth £439m (after rounding).

Given Chelsea’s sale for £2.5b in May 2022, it seems unlikely that a willing buyer would have been able to purchase their London rivals Arsenal for less than a fifth of that price. Even considering that Arsenal’s valuation would have been lower in May 2021, after they had just finished 8th in the Premier League, than it is now, this valuation still seems far too low.

Criticisms of this approach

As seen with the Arsenal example, the assets-based valuation approach can lead to undervaluation. The football specific reasons for this were discussed in the assets section of this article: the nil values of academy graduates and free transfers; player transfer fee inflation; the undervaluation of stadia; and non-recognisable internally generated intangible assets such as the club brand and fan databases.

Further, an assets-based valuation values a company on a particular date as provided on the balance sheet (often presented as 'Statement of Financial Position as at DD Month YYYY) and, in the UK, the accounts must only be filed 9 months after this date (or 6 months for a public company). Consider that the club won't publish financial statements for another year after the last set and it's possible that an assets-based valuation could be based on information that is up to 21 months out of date.

Assets-based approaches are retrospective and do not consider a company’s prospective earnings. Other valuation approaches such as income-based ones do take into account future performance.

Like a good football team, a company should be more than just the sum of its parts - but this is exactly how a company is treated under an assets-based method.

In other business settings, assets-based valuations are most commonly used in situations where a company is facing liquidation and may have to be ‘sold for parts’ to cover debt obligations. This seems like the most relevant setting for this valuation method.

Conclusion

After considering the numerous flaws of this approach, it is clear that using an assets-based valuation of a football club would be inappropriate. In fact, using an assets-based valuation of almost any company would be inappropriate - except in certain specific circumstances.

For some of the same reasons expressed here and for other reasons which are not, an assets-based valuation approach is not the only classical approach that fails to fairly express the value of a football club. I will address these other approaches in future articles.

Sources

The Price of Football, Kieran Maguire, @kieranmaguire on Twitter

How do you value a football club?, the Athletic

Accounting of typical transactions in the football industry, PwC

CIES

Investopedia

IFRS